Cathaoir Synge

It was the fourth day of our Irish holiday, and I was feeling wistful, because we had both come to know that the trip would mark the end of a romance which had been shaky at best.

Colleen was an Irish-American professor of theater, and she had wanted to show me all of her favorite spots in the Gaeltacht, an Irish-language region of the Emerald Isle. One of the places she loved was Inis Meáin, in the middle of the Aran Islands, a small group just off the western coast. Connoisseurs of fine woolen knitted sweaters would know of the area, perhaps preventing its descent into total obscurity.

Getting to this out-of-the-way locale was a bit of a chore - the ferry landed there only on certain days, since it was so far off the beaten track, and the trip included a lengthy stop at another island along the way. While waiting for the tide to advance to the point where it would be possible to dock at our island, we strolled hand-in-hand during the layover at Inis Oirr. It proved to be a bittersweet interlude - there was no use in discussing the end of something we both knew was dead, but we decided to make the best of our month-long journey together.

As we waited for the first mate to ready the small ferryboat for the next part of the voyage, it soon became apparent to both of us that the poor man had not been blessed with good looks. His hunchback, his immense hooked nose, and his manner in scuttling about the boat all reminded us of a certain horror movie. We simultaneously turned to each other, whispered "Igor!" - and shared a much-needed laugh.

The final leg of our trip was stormy and wind-tossed, as if to confirm the Gothic mood suggested by Igor's appearance. I knew we were going to a place where the twentieth century had made very few inroads, and the sense of isolation sharpened as Colleen slowly became seasick. After struggling against it for several minutes in the tiny cabin, she went out on deck to brave the high seas and christen the waves with the remains of her breakfast.

The captain was unsure whether conditions would allow a safe landing on our island, and indeed the docking was a bit dicey - we were the only two passengers to disembark, and the wind rocked the ferry alarmingly. They practically had to throw us up onto the cement pier, and our knapsacks were heaved up after us. We dusted ourselves off and leaned vigorously into the wind. After struggling past some rotting fish remains, we entered a narrow, paved path lined with six- and seven-foot walls of masterfully interlocked stones. We couldn't hear each other speak, but Colleen pointed up ahead, in the general direction of our destination. Through a small crack in the wall on our left, we could see the ruins of a tenth-century church, and I got the unsettling feeling that we had traveled far back in time.

A huge, slobbering canine charged from our right, and I think we both screamed, but an old crone with a toothless grin made motions that the dog was only being friendly. As we all continued to walk between the walls of stone, the wind quieted somewhat, and Colleen made an attempt to converse with the woman. Even though I was next to her, I couldn't hear a word, but it appeared that this dog owner was simply promenading her beast around the perimeter of the island, in what I judged to be near-hurricane conditions. We came to several paved cross-paths, all lined with the walls of stone, and Colleen indicated that we should turn and part ways with the old woman. We all waved goodbye, and I briefly wondered how anyone could find their way around in this confusing maze.

After some hot soup at the bed-and-breakfast cottage (which magically appeared out of nowhere), the wind calmed down and the weather even turned sunny. Colleen and I ventured forth, walking toward the hill of our small island, and she explained the stone walls. Many centuries ago, the place was covered only with rocks, but the first settlers were determined to make soil where none had existed before. So they dragged seaweed out of their fishing nets, carefully placing walls of the all-too-plentiful stones around it, and left it to rot in the intermittent sunshine. Over the course of many years, the fences of stone, crucial for keeping the newly-formed compost from blowing away in the constant windstorms, were extended to form a continuous crosshatch of tiny pastures all over the island. Most of the fields were not much larger than a small house, and the crazy patchwork was broken at irregular intervals with paths connecting various areas. Sheep and other farm animals were ferried in, and an agrarian/fishing culture clung tenaciously to life on this tiny outpost.

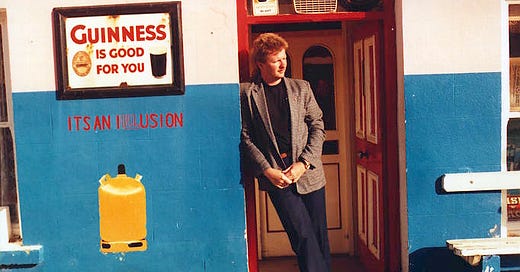

Daily life was harsh, and most of their young folk were leaving for the excitement of cities on the mainland or in America, but the ones who remained were amazingly tough and taciturn. They drank silently in the island's one pub, and very infrequently they would sing, if the hour got late enough, and the Guinness held out. Their voices were heartbreakingly beautiful, crooning the ancient songs in the ancient tongue.

Today, Colleen and I were headed toward the far end of the island, where the famous Irish playwright John Millington Synge ("Playboy of the Western World") often withdrew to write. He had a summer residence on Inis Meáin at the turn of the century, to escape the pressures of civilization on the mainland, and his sojourns were proudly documented with several Irish-language signs. One pointed the way to his thatched-roof cottage; another, down the path leading to his favorite writing retreat.

During our walk, Colleen regaled me with stories of her last stay - after one late-night songfest in the pub, she said she found herself face to face with the ghost of Synge, near dawn at the entrance to his old cottage. She was a very down-to-earth and practical woman, and she couldn't logically explain her certainty that she had been in the presence of the great man himself. This streak of mysticism in an otherwise severely rational academic was suddenly appealing, and I suggested that we climb a few rock fences to find a deserted field.

The denizens of the island had become experts in stonemasonry over the millennia, and had built unobtrusive step-stones into the sides of the walls. These steps led up to small notches that a person could fit through, but which would foil any escape attempt by the sheep. After crossing several notches, we found ourselves at the open entrance to a tiny field-inside-a-field. Evidently there had been too many rocks remaining when the farmer had finished his outer wall, so he had erected a smaller inner enclosure, just to clear the area of leftover stones.

No-one was visible for at least a mile, and we were delighted with our own little private "fort," so we ogled each other hungrily as we quickly shed our clothes. But afterward, the flattened wildflowers seemed unbearably melancholy. We dressed while studiously avoiding each other's eyes, and slipped quietly away from the ground we had desecrated.

A few minutes later, we arrived at the end of the path which announced "Cathaoir Synge." It was anticlimactic - a semi-igloo of stones had been erected at the top of a promontory facing across to the outer island of Inis Mór. When Colleen crawled inside Synge's "chair" to steep herself in meditation on the playwright, I climbed a little way further down the cliff and watched the seagulls soaring above the crashing waves two hundred feet below.

I became lost in a cheerless reverie, and didn't notice one gull, inching closer and closer in her weaving flight path across the cliff, until she was almost in my face. I threw my hands up automatically - the bird stalled dead in midair, and wheeled away, startled enough for the two of us. I kept an eye on her, and after a few minutes she was back, at a more comfortable distance. I extended my hands again, partly to reassure myself and to make light of my earlier shock. She executed the same stall-and-wheel maneuver. When she returned a third time, we each played our parts again, and I began to suspect that I might be too near an egg-filled nest which she was protecting. So I backed off to the top of the cliff, but the gull followed...

As I walked from one side of the bluff to the other, it became obvious that I was drawing her away from the comfortable soaring of the windy updrafts into a relatively calm area behind the crest. She was working harder to fly, trying to continue the game we had started, and I gradually realized that I wasn't threatening her nest - she just wanted to play! To test this, I climbed back down to my original position on the cliff, and she moved a little further away, unconcerned. If anything, it seemed as if she was grateful that I had moved back into the updrafts, where it was somewhat easier for her to stay aloft. She lined herself up for another approach, I threw my hands skyward at the appropriate moment, and she stalled and wheeled. She was just a few feet away - close enough so I could see the energy she was investing to play the game. She exerted twice the effort of the other seagulls, who were lazily banking and circling as the wind took them. But she seemed to enjoy it, and I was having a grand time participating in a simple entertainment which this member of another species was generously bestowing upon me.

We continued for twenty or thirty minutes, until I became aware that Colleen was snapping pictures of us from the Cathaoir. I smiled up at her, she smiled at me, and our sadness was mended. I climbed back to the top, took Colleen's hand, and returned to the path, with the seagull drifting close behind. As we walked, I apologized to the gull for ending our game, and earnestly explained why she couldn't follow us back home. Colleen gifted us both with gales of laughter.